by Dalip Malik CPA | Jan 14, 2019 | Tax Tips and News

Tax Policy – Ocasio-Cortez’s Proposed 70 Percent Top Marginal Income Tax Rate Would Deter Innovation

As America’s advantage in innovation erodes and levels of entrepreneurial activity decline, it is becoming increasingly important that tax policy does not further hinder economic dynamism. Unfortunately, a recent proposal by freshman Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) to increase the top income tax rate to 70 percent would unmistakably do this. In addition to making dubious claims about tax history, advocates of this proposal ignore that a high top marginal income tax rate would deter innovative activity, including the work of inventors and entrepreneurs.

The congresswoman’s proposal is arguably based on the work of economists Emmanuel Saez and Peter Diamond, who claim that the optimal tax rate for maximizing revenue is 73 percent. This work does not account for the incentive to enter high-earning occupations.

Individual decisions to enter an occupation include weighing the expected return of one’s effort and educational investments and the cost of forgoing alternative opportunities. Saez and Diamond consider this but say there is limited economic data to determine how high top marginal income tax rates impact long-run decisions such as investing in education or becoming an entrepreneur.

High top marginal income tax rates could make some people reconsider their plans to upgrade their skills or try to implement a risky business idea. There are at least two forms of innovative activity deterred by a higher top marginal income tax rate: the generation of new ideas and formation of entrepreneurial ventures.

New ideas are often formed and implemented by individuals working in applied research, such as a medical doctor researching a cancer treatment or a materials scientist building a smaller lithium-ion battery. It requires a significant investment in time and energy to discover and refine an innovative idea, but the expected return is high. A higher top marginal income tax rate reduces this expected return, and makes alternative opportunities look more attractive for would-be innovators. Fewer of them would think the investment is worth the expected return.

A 70 percent top marginal rate would also deter potential entrepreneurs, who must invest high levels of time and effort into an innovative firm. These entrepreneurs often take new ideas and merge them with a sound business model in search of profit. As Stanford economist Charles Jones explains, “High incomes are the prize that motivates entrepreneurs to turn a basic research insight that results from formal [research and development] into a product or process that ultimately benefits consumers.”

The economic literature confirms that higher marginal income tax rates have a negative impact on innovation. Marginal tax rates weigh heavily on inventors when deciding where to locate, and empirical evidence suggests that “higher personal and corporate income taxes negatively affect the quantity and quality of inventive activity and shift its location at the macro and micro levels.”

These activities benefit more than just the inventors or entrepreneurs. Innovative activity increases incomes across all levels, as a productive idea is replicated and circulates throughout the economy in the form of higher worker productivity, output, and incomes.

Advocates of a 70 percent top marginal income tax rate take high-income earners as a given, forgoing the costs and risks these earners incurred to obtain that income. While any tax on high earners may deter some innovative activity, it is important that we consider what trade-offs we are making when we consider raising the top rate. A 70 percent top marginal income tax rate would make many potential inventors and entrepreneurs abandon their plans to invest in human capital, invent technologies, and form innovative businesses, to their detriment and to the detriment of society.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Ocasio-Cortez’s Proposed 70 Percent Top Marginal Income Tax Rate Would Deter Innovation

by Dalip Malik CPA | Jan 14, 2019 | Tax Tips and News

Tax Policy – Tax Relief is on the Agenda in Austria

Last week, the Austrian cabinet met to plan the political agenda for 2019 and outline plans for changes to tax policy that will take place over the next few years. The current government has been in place since the end of 2017, and tax reform has been a main part of the agenda since. At the close of the cabinet meetings, the government reaffirmed its commitment to tax relief for low-income workers and efforts to make Austria more attractive to business investment. The government plans to reduce the tax and social security contribution share of GDP to 40 percent by 2022. In total, Austria collected 41.8 percent of GDP in tax revenue in 2017.

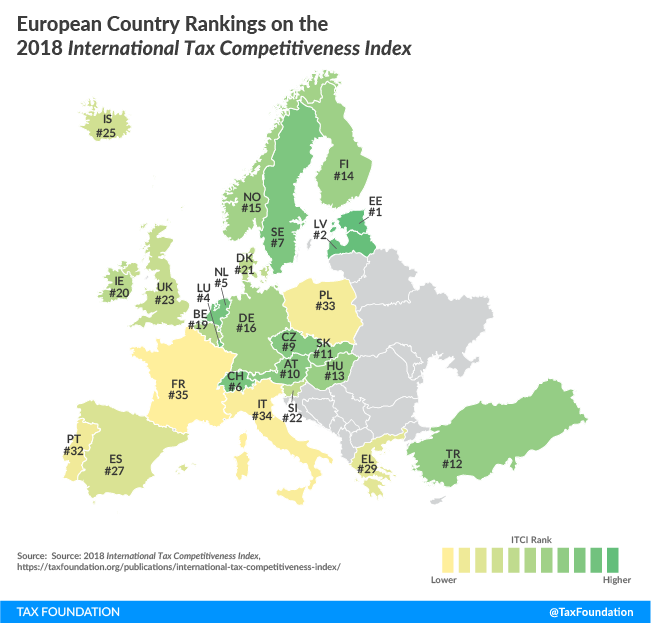

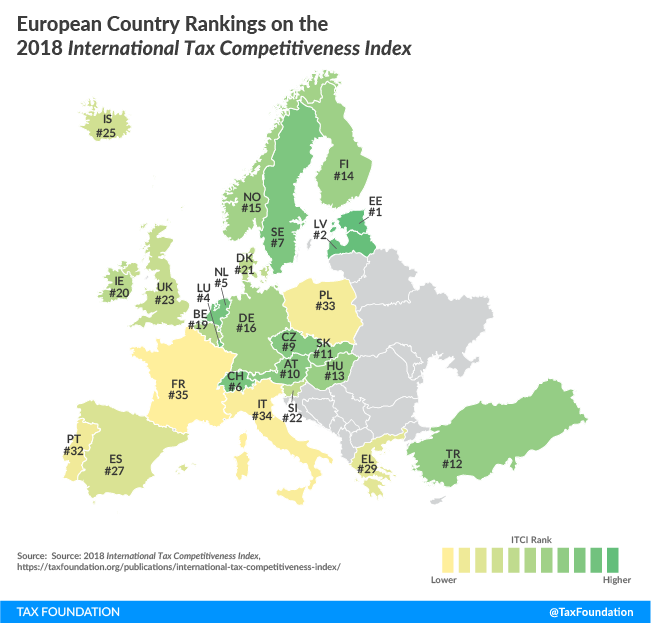

Austria currently ranks 10th on our International Tax Competitiveness Index, but weaknesses in business taxation (ranked 15th) and personal income taxation (ranked 21st) present opportunities for Austria to reform its tax system to be more neutral and pro-growth.

In total, the government plans to provide €6 billion (US $6.9 billion) in tax relief from 2019-2022, €1.5 billion ($1.7 billion) of which went into effect on January 1 as part of changes to tax benefits for families. In 2020, another €700 million ($803 million) in tax relief for low-income workers will be put in place. The remaining tax relief will come in changes to the current tax brackets and system of business taxation. The details of these proposals will come later, but eliminating bracket creep and providing tax relief for reinvested earnings are included in the plans.

In all, by 2022, the government expects 4.5 million taxpayers to benefit from reforms. Beyond lesser tax burdens, there will also be measures to simplify taxation to minimize the burden of filing—especially for small businesses and lower-income individuals.

A separate tax proposal that is included in the agenda is a tax on digital advertisers. Currently, Austria levies a 5 percent sales tax on advertising, but this applies to ads placed in traditional forms of media (print, tv) rather than online advertising.

Under the new proposal, the rate on ad sales would be lowered to 3 percent and would apply to the current tax base as well as sales of digital advertisements by some large companies. Companies that have at least €750 million ($860 million) in worldwide revenue and €10 million ($11.5 million) in revenue from sales in Austria would be required to pay the tax on digital ad sales. Chancellor Kurz has specifically stated that the tax on digital ad sales will not apply to Austrian businesses. However, this tax would be a burden faced by those who purchase ads from large foreign digital advertising companies rather than the companies themselves.

The proposal to target digital companies is not surprising given that Austria worked last year to get agreement on the digital services tax proposal at the European level. Some of the same criticisms of that broader proposal from the European Commission would apply to the new Austrian proposal. It seems counterproductive to be designing new ways to tax digital giants at the same time that Austria is trying to promote digitalization. The ultimate burden of a sales tax falls on consumers, so the government is really proposing to raise taxes on those who purchase digital ads rather than the companies that supply those ads.

In all, the Austrian government has laid out a strong vision for tax policy changes over the next few years. It will be important to keep the agenda focused on making the system more neutral and competitive rather than creating new distortions, and we’ll continue to monitor developments and update our analysis over the coming days.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – Tax Relief is on the Agenda in Austria

by Dalip Malik CPA | Jan 14, 2019 | Tax Tips and News

Tax Policy – How Much Revenue Would a 70% Top Tax Rate Raise? An Initial Analysis

Congresswoman Ocasio-Cortez recently discussed her support for taxing incomes over $10 million at 70 percent. Her goal is to raise additional revenue to fund new federal priorities, such as a “Green New Deal,” which aims to convert the U.S. economy to fully renewable energy. There has been discussion over how much such a proposal would raise in revenue. For example, the Washington Post published estimates stating that a top rate of 70 percent could raise a little more than $700 billion over a decade. However, current estimates do not account for behavioral effects, which are important to evaluate a policy like this. This is because a tax rate that high could encourage individuals to shelter their income, thus reducing potential revenue from this proposal.

Details of the Proposal

So far, Congresswoman Ocasio-Cortez has not been specific about her proposal for a 70 percent tax rate. However, her comments imply that she wants to add an eighth tax bracket of 70 percent on incomes over $10 million. What this means is that individuals would need to pay 70 cents for every dollar they report in taxable income over $10 million. It’s not clear yet whether it would apply only to ordinary income (wages, salaries, interest, business income), or if it would apply to all income (ordinary income plus long-term capital gains and qualified dividends).

Given the uncertainty around what income this top tax rate would apply to, we estimated two potential proposals. Proposal 1 would add an 8th tax bracket of 70 percent over $10 million on ordinary income. Qualified income would remain taxed at a top rate of 20 percent. Proposal 2 would add an 8th bracket of 70 percent over $10 million but apply it to all income—both ordinary income and qualified income. Both proposals would be applied to taxable income over $10 million and the brackets would not be adjusted for filing status. The threshold would remain $10 million whether a tax filer was single or married filing jointly.

| Proposal 1 |

Proposal 2 |

|

Add an 8th tax bracket at 70 percent on taxable income over $10 million for all filing statuses. Applies to only ordinary income. Bracket widths are not adjusted for filing status.

|

Add an 8th tax bracket at 70 percent on taxable income over $10 million for all filing statuses. Applies to ordinary income and qualified income. Bracket widths are not adjusted for filing status.

|

Conventional Estimate

We estimate that applying a new 70% tax rate on ordinary income over $10 million (proposal 1) would raise about $291 billion between 2019 and 2028. While taxpayers would react to proposal 1 by reducing taxable income, the effect wouldn’t be significant. As a result, the proposal would still raise revenue each year over the budget window.

Counterintuitively, if the 70 percent tax bracket were to apply to all income over $10 million, the proposal would raise much less revenue. We estimate that proposal 2 would raise $51.4 billion between 2019 and 2028 and lose revenue in the first two years of its enactment.

Conventional Revenue Estimate of Two Proposals to Raise the Top Tax

Rate to 70 percent for Income over $10 Million (Billions of Dollars)

|

Note: Both Proposal 1 and 2 would apply a 70 percent tax on incomes over $10 million. Proposal 1 would only apply the new tax to ordinary income. Proposal 2 would apply the new tax to all income (ordinary plus capital gains and dividends). Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, October 2018

|

| |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

2026 |

2027 |

2028 |

2019-2028 |

|

Proposal 1

|

22.2 |

23.9 |

25.4 |

27.3 |

29.5 |

31.8 |

34.3 |

29.4 |

32.8 |

35.1 |

291.7 |

|

Proposal 2

|

-10.4 |

-4.6 |

4.3 |

5.6 |

7.1 |

8.7 |

10.4 |

8.1 |

10.2 |

12.0 |

51.4 |

The reason why a 70% tax rate on all income over $10 million would raise very little revenue is due to how taxpayers would react to the much higher tax rate on capital gains. Under current law, capital gains are taxed only when they are “realized” — that is, when the assets are sold. This means that individuals can effectively choose when to pay the tax. As a result, capital gains are very responsive to the tax rate.

For capital gains over the $10 million threshold, the tax rate would increase from the current 23.8 percent (the 20 percent statutory tax rate plus the 3.8 percent net investment income tax) to 73.8 percent. That is a 210 percent increase. This would result in a significant decline in capital gains realizations that would otherwise be subject to the new tax rate. We estimate that realizations that would be subject to the $10 million tax bracket would be permanently 77 percent lower than they otherwise would have been. As a result, federal income tax revenue from capital gains would fall and offset a large portion of the additional tax revenue from taxing ordinary income.

Dynamic Revenue Estimate

On a dynamic basis, we estimate that Proposal 1 (applying the top tax rate to only ordinary income) would raise $189 billion between 2019 and 2028. In contrast, we estimate that Proposal 2 would end up losing $63.5 billion over the same period.

Dynamic Revenue Estimate of Two Proposals to Raise the Top Tax Rate

to 70 percent for Income over $10 Million (Billions of Dollars)

|

Note: Both Proposal 1 and 2 would apply a 70 percent tax on incomes over $10 million. Proposal 1 would only apply the new tax to ordinary income. Proposal 2 would apply the new tax to all income (ordinary plus capital gains and dividends). Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, October 2018

|

| |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

2026 |

2027 |

2028 |

2019-2028 |

|

Proposal 1

|

19.3 |

17.8 |

15.9 |

17.3 |

19.0 |

20.7 |

22.8 |

16.4 |

19.0 |

20.7 |

189.1 |

|

Proposal 2

|

-13.5 |

-11.1 |

-5.8 |

-5.2 |

-4.5 |

-3.7 |

-2.7 |

-6.6 |

-5.7 |

-4.7 |

–63.5 |

Proposal 1 would increase the marginal tax rate on wage income, which would reduce hours worked by taxpayers impacted by this tax bracket. In addition, the cost of noncorporate capital would rise as profits from noncorporate businesses would be taxed at a much higher rate. Both effects would narrow the income and payroll tax base, resulting in less additional revenue than on a conventional basis.

Proposal 2 would have similar economic effects as proposal 1. The marginal tax rate on wages and the cost of capital for noncorporate businesses would both be higher. In addition, proposal 2 would also impact the corporate cost of capital by applying the higher tax rate to capital gains and dividends. However, that additional impact due to the taxation of capital gains and dividends would be small. Individuals who react by deferring capital gains would greatly reduce their effective tax rate or, ultimately, completely avoid the tax through step-up in basis at death.

The reason proposal 2 ends up losing revenue is not because the negative dynamic feedback is particularly large. In fact, the dynamic feed back of proposal 1 and proposal 2 are very similar. The reason proposal 2 ends up losing revenue is because the tax base, on a conventional basis, is narrower to start with due to much lower capital gains realizations. Once the negative dynamic revenue feedback is incorporated, revenue for the federal government ultimately falls.

Methodology and Modeling Notes

We use the Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Tax Model to estimate the impact of tax policies. The model can produce both conventional and dynamic revenue estimates of tax policy. The model can also produce estimates of how policies impact measures of economic performance such as GDP, wages, employment, the capital stock, investment, consumption, saving, and the trade deficit. Lastly, it can produce estimates of how different tax policy impacts the distribution of the federal tax burden.

Our estimates assume that taxpayers will adjust their behavior to the new tax rate. There are two behavioral effects important for analyzing this proposal.

The first important behavioral effect is how taxable income, in general, responds to taxation. When faced with an increase in taxes, individuals will respond by adjusting their taxable income downward to avoid the tax.[1] The responsiveness of taxable income to the tax rate is typically expressed as an elasticity. These elasticities of taxable income (ETI) are expressed as the percent change in taxable income relative to the percent change in the “net-of-tax-rate.” For example, a proposal may increase the top tax rate from 37 percent to 50 percent. This means that the net-of-tax rate would fall by 20.6 percent.[2] With an elasticity of .25, we would expect taxable income to fall by 5.1 percent.[3] In the literature, ETIs are not typically very high. A 2012 review of the literature finds that they range from 0.12 to 0.4 with a mid-point of 0.25. [4] For this analysis we use the mid estimate of 0.25, which is consistent with other groups.[5]

The second important behavioral effect is how capital gains realizations respond to changes in tax rates. Under current law, capital gains are only taxed when realized. As a result, taxpayers can choose when to realize their gains and pay the tax. This makes capital gains significantly more responsive to tax rates than other types of income. This behavior is also expressed as an elasticity. An elasticity of -0.9 means that for a 10 percent change in the capital gains tax rate, realizations would fall by roughly 9 percent (10% * -0.9). There is a wide range of estimates in the literature with a distinction between short-run realizations behaviors and long-run realization behaviors. Elasticities can be as high (in absolute value) as -6.4 and as low at -0.3. That Tax Foundation’s preferred elasticities are -1.1 in the first year, -0.9 in the second year, and -0.7 in all subsequent years, which are consistent with other group’s assumptions.[6]

In modeling the proposal’s impact on the labor force, we used an elasticity of 0.22, which is lower than our typical elasticity of 0.3. This lower elasticity is consistent with CBO’s elasticity for high-income workers and reflects the belief the high-income wage earners are less sensitive to marginal tax rates than lower-income wage earners and especially secondary earners.[7]

Given the limited amount of details about the proposal, this is a preliminary analysis. The ultimate impact of the proposal will depend on its final details.

[1] Aparna Mathur, Sita Slavov, and Michael Stain, “Should the Top Marginal Income Tax Rate Be 73 Percent?” http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/-should-the-top-marginal-income-tax-rate-be-73-percent_085518416524.pdf

[2] (1-50%)-(1-37%)/(1-37%)

[3] -20.6% * 0.25

[4] Emmanuel Saez, Joel Slemrod, and Seth H. Giertz, “The Elasticity of Taxable Income with Respect to Marginal Tax Rates: A Critical Review.” Journal of Economic Literature. 2012.

[5] Tax Policy Center, “Brief Description of the Tax Model,” Updated on August 23, 2018. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/resources/brief-description-tax-model

[6] Ibid. Also see: Tim Dowd, Robert McClelland, and Athiphat Muthitacharoen, “New Evidence of the Tax Elasticity of Capital Gains,” June 2012. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/112th-congress-2011-2012/workingpaper/43334-taxelasticitycapgains.pdf

[7] Congressional Budget Office, “How the Supply of Labor Responds to Changes in Fiscal Policy.” October 2012. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/112th-congress-2011-2012/reports/43674-laborsupplyfiscalpolicy.pdf

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – How Much Revenue Would a 70% Top Tax Rate Raise? An Initial Analysis

by Dalip Malik CPA | Jan 11, 2019 | Tax Tips and News

Tax Policy – America Already Has a Progressive Tax System

Policymakers at the federal level have expressed interest in raising the tax burden on high-income individuals. For instance, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) recently proposed raising the top marginal income tax rate to 70 percent.

What these debates sometime gloss over is that the U.S. federal tax system is already progressive. Under current law, high-income taxpayers pay a larger share of the tax burden, while lower- and middle-income individuals shoulder a relatively smaller tax burden. This is true both for federal income taxes and the federal tax code overall. Furthermore, such a high-rate, narrow-base proposal is unlikely to generate a large amount of revenue.

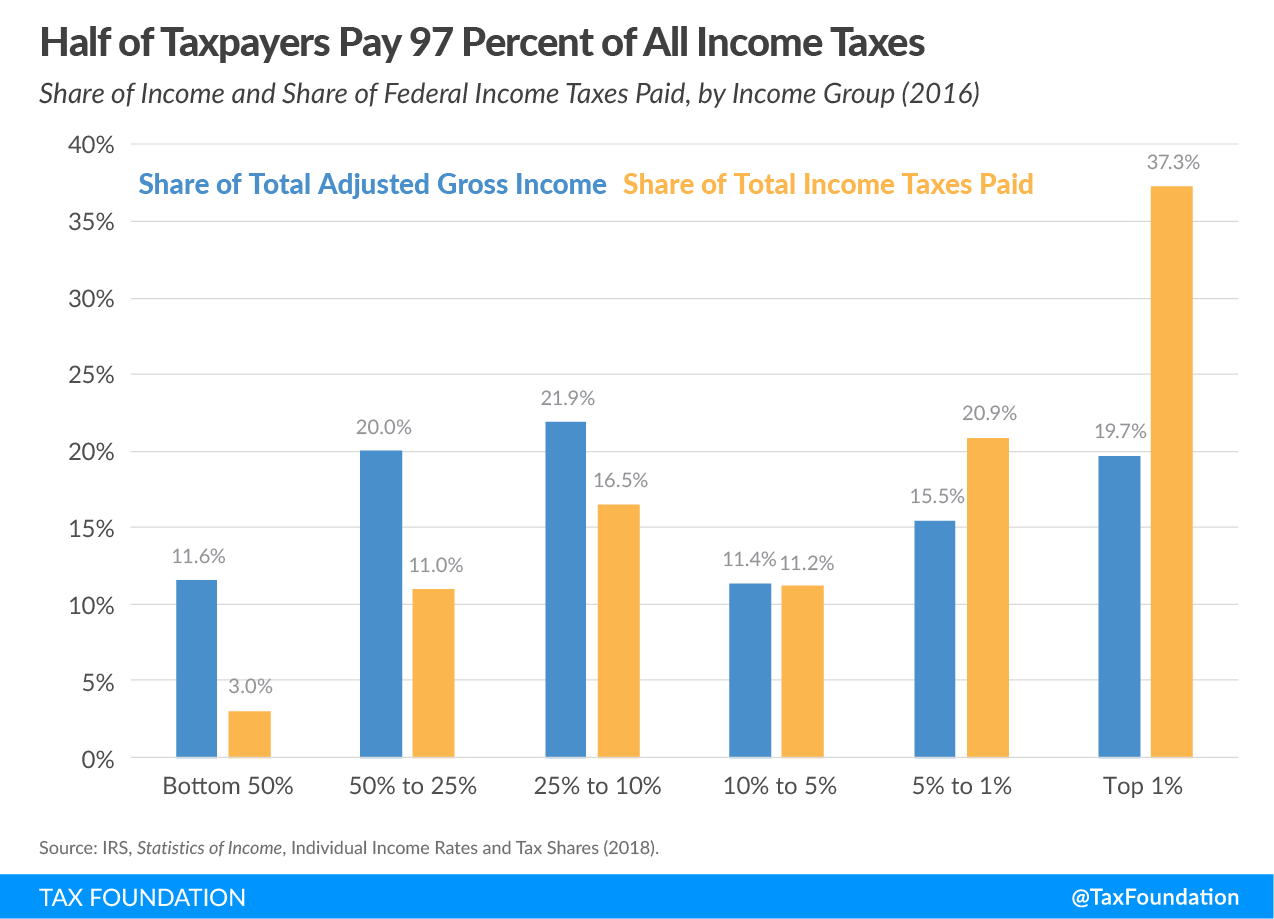

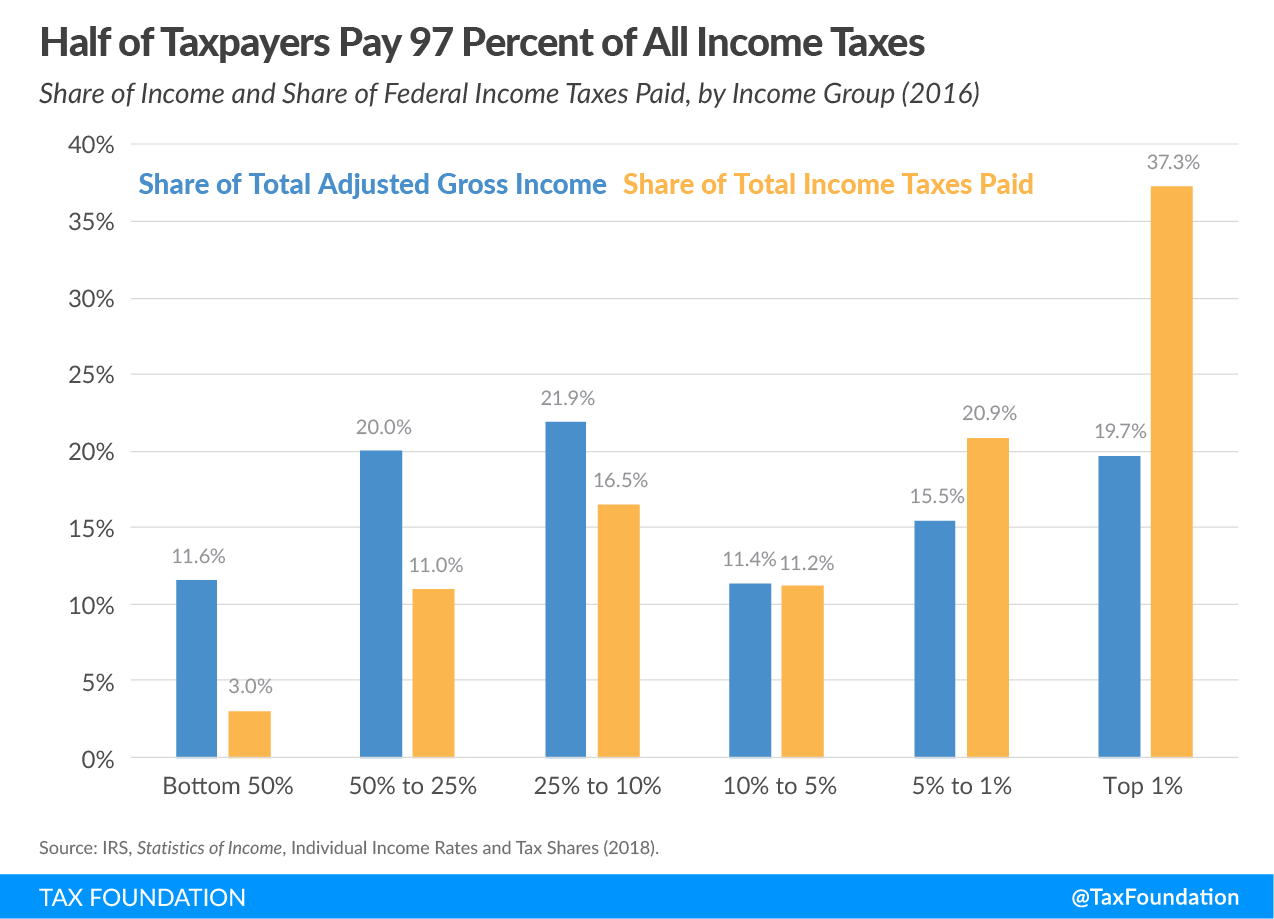

The chart below illustrates how progressive the income tax system is today, as well as which income groups generate the most revenue. In 2016, the bottom 50 percent of taxpayers—those with adjusted gross incomes (AGI) below $40,078—earned 11.6 percent of total AGI. However, this group of taxpayers paid just 3 percent of all income taxes in 2016.

In contrast, the top 1 percent of all taxpayers (taxpayers with AGI of $480,804 and above), earned 19.7 percent of all AGI in 2016, and paid 37.3 percent of all federal income taxes. The top 1 percent of taxpayers accounted for more income taxes paid than the bottom 90 percent combined, who paid 30.5 percent of all income taxes.

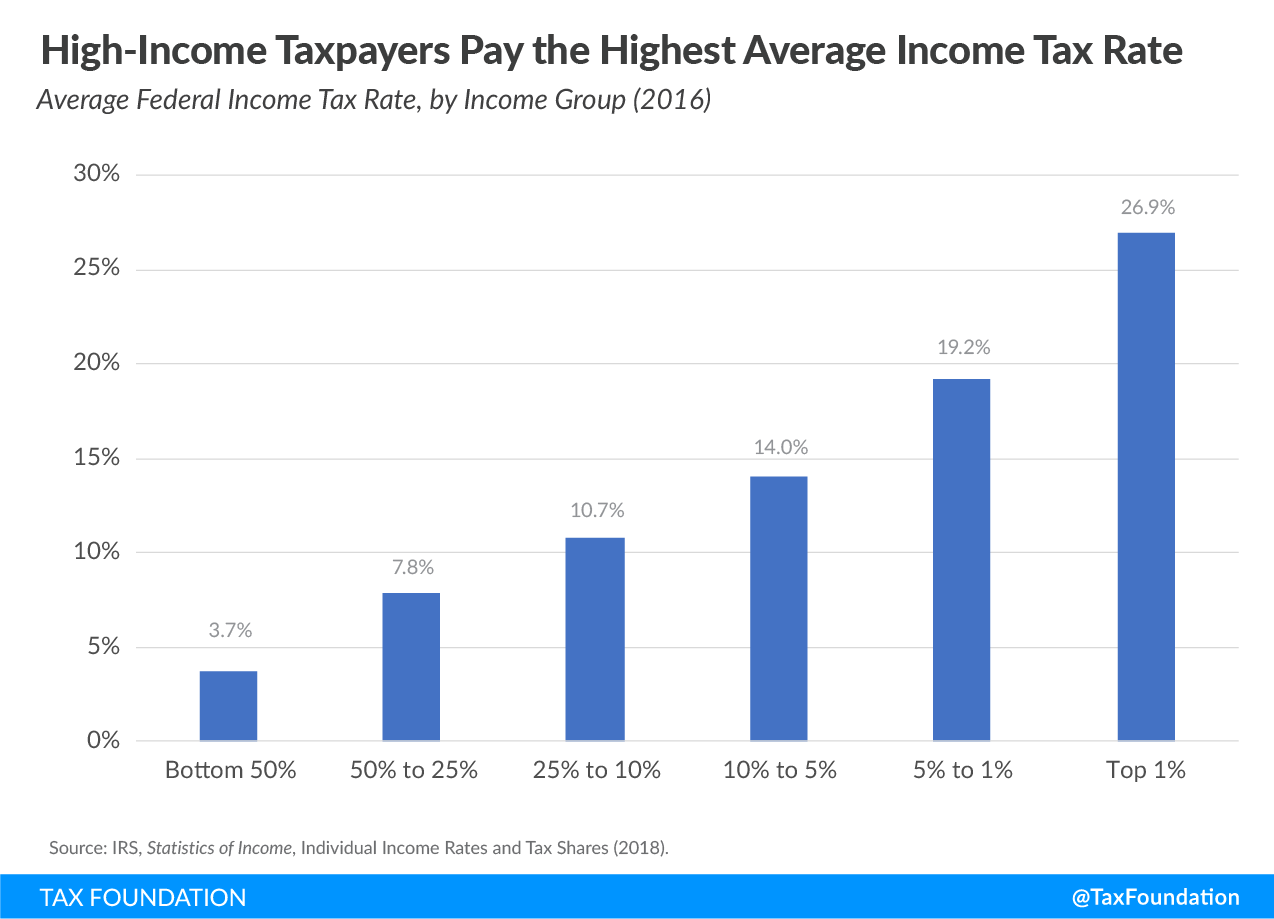

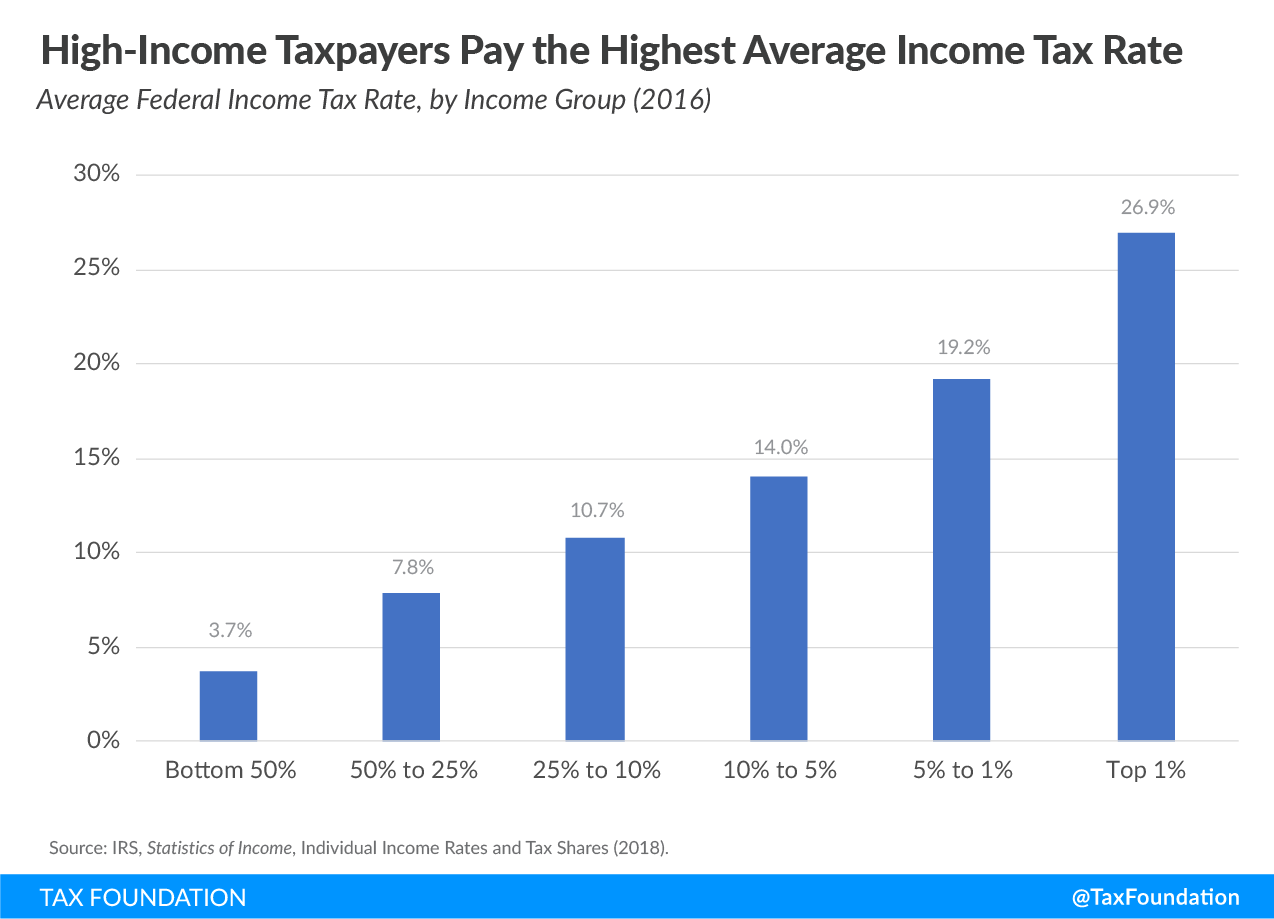

Additionally, as household income increases, average income tax rates rise. For example, the bottom 50 percent of taxpayers (taxpayers with AGIs below $40,078) faced an average income tax rate of 3.7 percent, while taxpayers with AGIs between the 10th and 5th percentiles ($139,713 and $197,651) paid an average rate of 14 percent. The top 1 percent of taxpayers (AGI of $480,804 and above) paid 26.9 percent, more than seven times the rate faced by the bottom 50 percent of taxpayers.

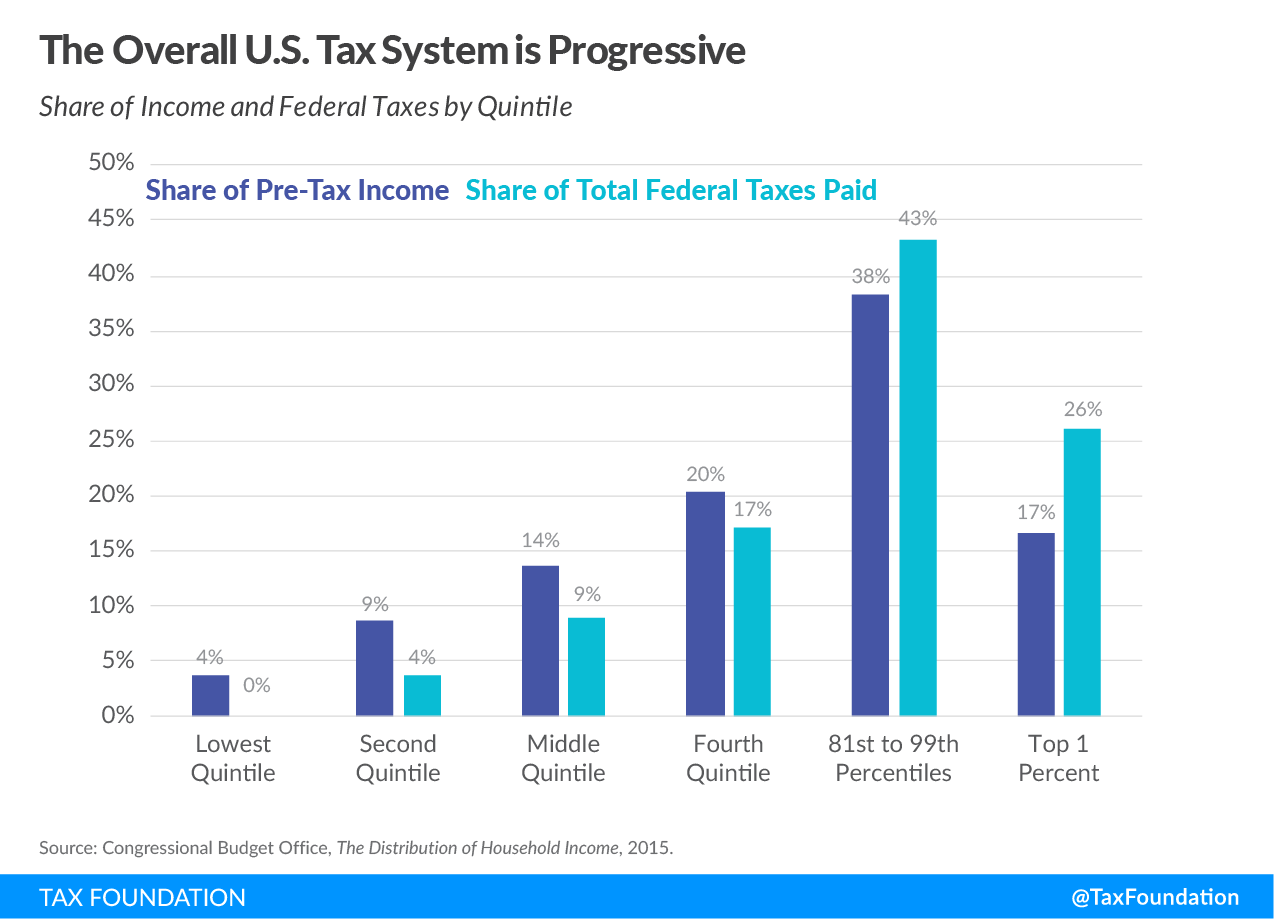

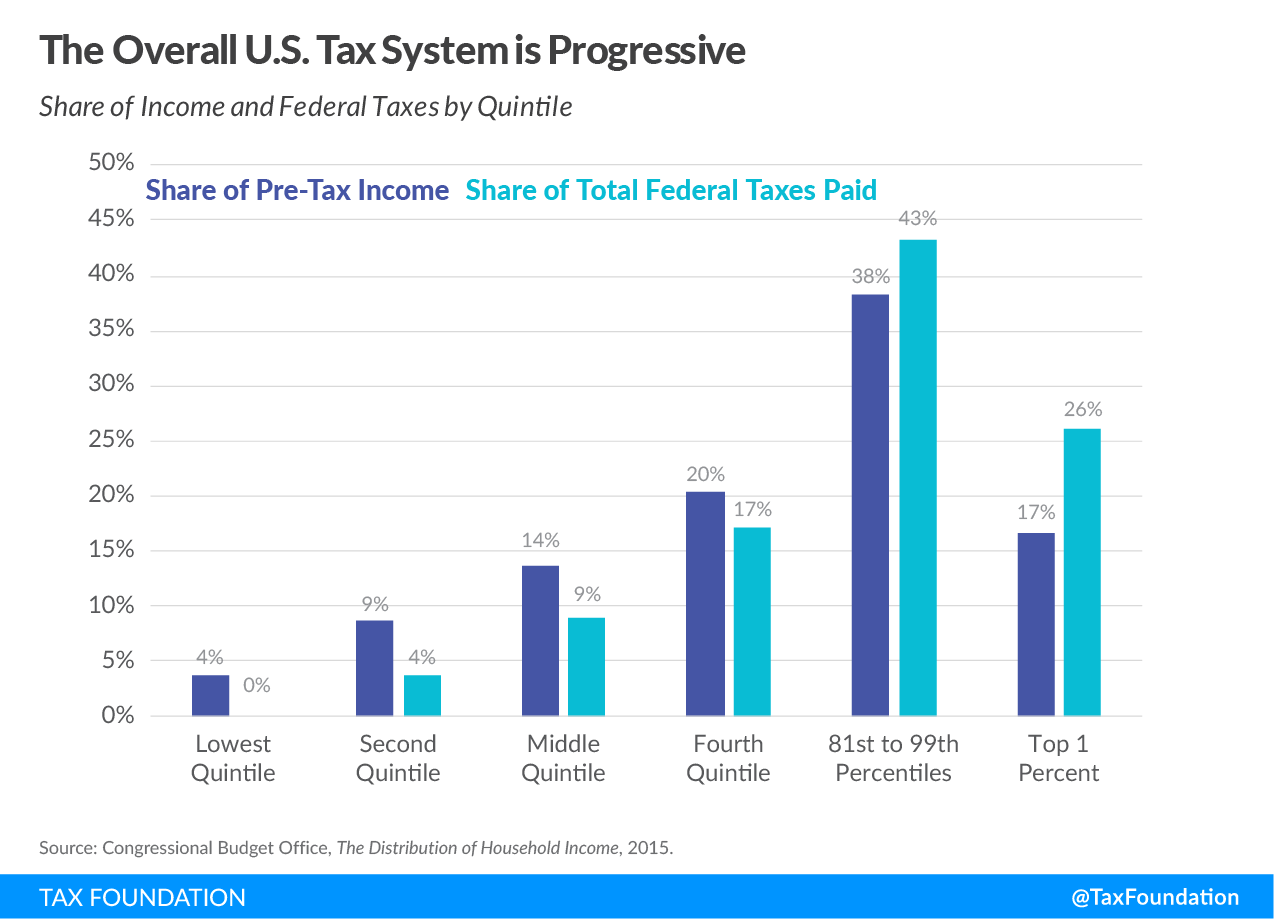

If the tax system weren’t progressive, each income group would bear a more similar share of the total tax burden equal to its share of the nation’s income. However, as the chart below (based on a recent study by the Congressional Budget Office) shows, when we account for all federal taxes—including excise and payroll taxes that tend to be more regressive—high-income taxpayers still bear a disproportionate share of the total burden.

Households in the lowest quintile earned 4 percent of the nation’s income in 2015, while they paid less than 0.5 percent of all federal taxes. Households in the third quintile earned 14 percent of national income and shouldered 9 percent of all federal taxes. Even upper-middle class, consisting of households in the fourth quintile, bore a lower tax burden than their share of national income.

The top 20 percent of households, in contrast, paid 43 cents of every $1 of federal taxes of all kinds, such as individual income, payroll, excises, and corporate income. As with the income tax, this share was greater than their share of the nation’s income, or 38 percent. The top 1 percent of households paid 26 percent of all federal taxes, more than their 17 percent share of the nation’s income.

Any fruitful tax reform discussion must acknowledge of how our tax code works, and which groups pay most. Legislators should keep in mind the tradeoffs involved with trying to raise revenue from a small number of taxpayers, and the challenge of raising substantial revenue without broad-based taxes on all Americans. As these charts show, the present distribution of the tax burden is quite different from what many might think.

![]()

Source: Tax Policy – America Already Has a Progressive Tax System